As UniServices celebrates the doubling of the University of Auckland Inventors’ Fund from $20 million to $40 million, the development and commercialisation of this technology is an example of real-world impact the University can have.

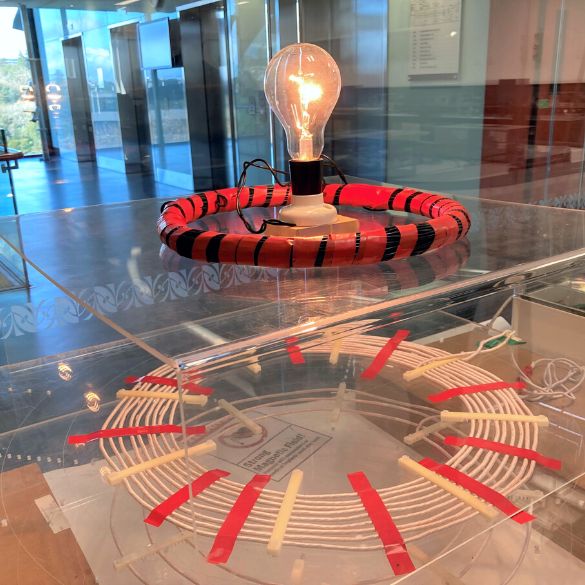

The basic concepts of wireless or inductive power transfer (IPT) have been known for more than a century. However, Auckland researchers have led the world in making wireless power transfer commercially useful and scalable to industry, says UniServices Executive Director of Commercialisation Will Charles.

The impact has already been immense within industry, making factories safer and production cheaper. The technology is now becoming more visible to consumers through wirelessly charged electronics, while wireless charging of electric vehicles is set to have enormous impact on our future.

The University of Auckland currently holds 294 granted patents and 92 live applications in the wireless power space, covering inductive, resonant transfer, bi-directional power transfer, magnetics and controllers.

“The commercial development of IPT technologies has transformed a number of industries and I would argue that it was first usefully invented here,” says Charles, who has been in his role since 2005 and has been instrumental in bringing IPT technologies to market. “The first team to show that it could be done usefully and scaled into industry was from the University of Auckland.”